Hopper’s paintings as virtual images: realism all too un-real

“The memory of his paintings tyrannizes over the scene itself. One begins to see Hopper’s paintings everywhere’’- New York Times ( 1964 )

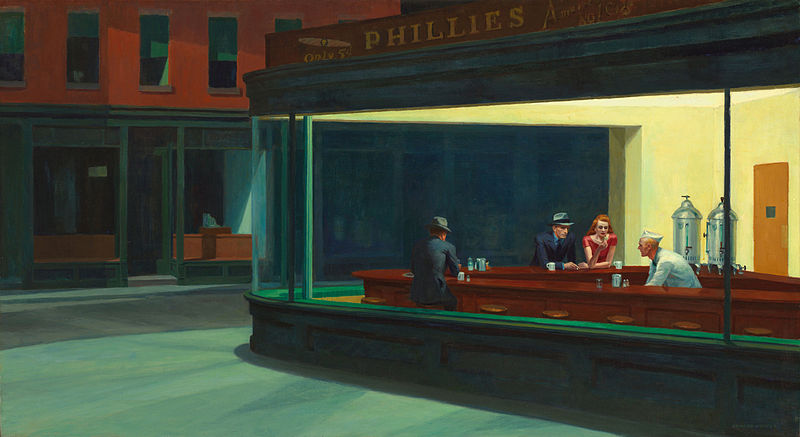

Edward Hopper’s paintings have long been a matter of cultural interest due to his influence on younger painters, photographers, and filmmakers, and authors of an ever-growing body of texts on Hopper tend simply to note or discuss his place in pop culture while scholars have shied away from making theoretical analysis of his paintings. But since the 1980s, talking about Hopper’s paintings has taken a significant turn to a new path with the advent of postmodern theories of image study. With the emergence of the concept of image as ‘virtual’, the distinction of its meaning from that of the painting, the performative function of Hopper’s paintings, and their phantasmatic effects on the viewers have been the topic of conversation in the art and media world. By looking at Edward Hopper’s paintings namely the ‘Nighthawks’ and the ‘Morning sun’ I will try to portray how the characteristics of virtual images of his paintings create a performative engagement with the audience by introducing the ‘screen’ as a medium to cause desire - a quintessential technique of the cinema.

Nighthawks ( 1942 )

Nighthawks ( 1942 )

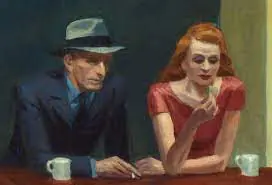

In this oil painting, four subjects are inside a downtown diner open late at night amidst the dark and deserted streetscape. The subjects are viewed through the diner’s large glass window, which is the only source of light in the painting. The crystal clear glass window gives the viewers direct access to the happenings inside the diner, enframing the actions of the subjects, thus acting as a cinematic screen that separates the audience from those who remain on the ‘other’ side window of the screen. The lack of any distinct signifier of these characters’ identity allows us to dive into our very own realm of imagination - we are introduced to our fantasy surrounding the predicament of these characters. We not only ‘see’ them doing their activities but we also ‘imagine’ them as acting.

What is the lonely man thinking?

What is the relationship between the man and the woman who remain so close to each other yet so distant?

The only source of light from the diner resembles how Hopper would keep his studio lights on at night even when the entire city would opt for blackouts as a security measure after the Pearl Harbour bombing during the dreaded times of the war. Just like Hopper’s desire would light up his studio even during unprecedented times, the nighthawks resemble the painter’s desire, still at play, glowing in the dark. But what are the nighthawks’ desires? All of Hopper’s paintings do not reveal anything about his subjects’ desires, but we watch them desiring.

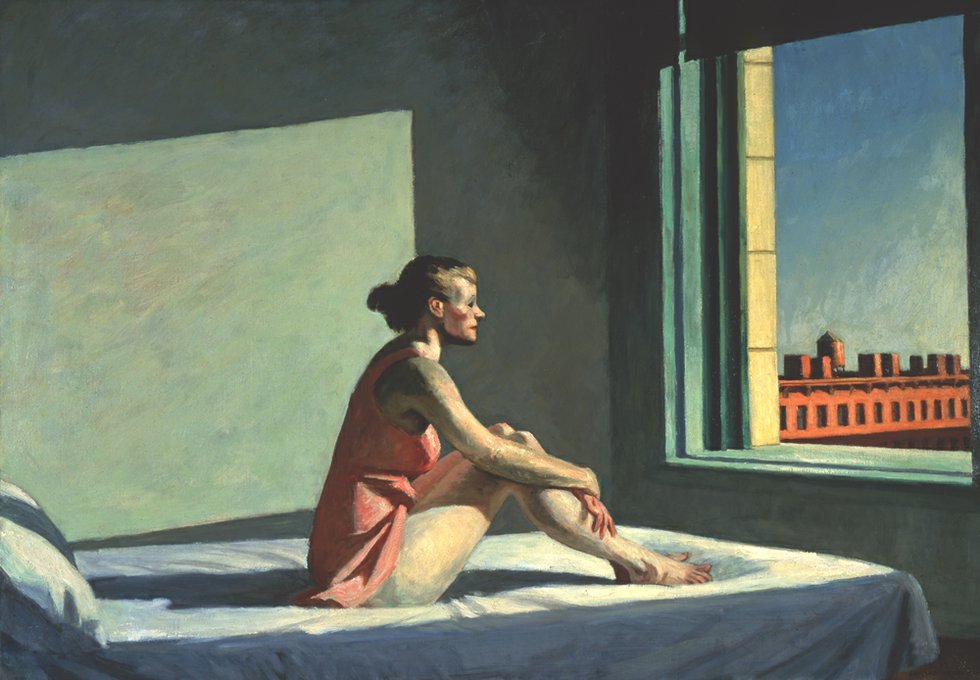

Below is another fabulous painting of his, namely the ‘Morning sun’ where we can find all the phantasmatic traits of ‘Hopper’s desire’.

Morning Sun ( 1952 )

Morning Sun ( 1952 )

In Morning Sun, a woman wearing a pink dress ( who is modeled after Hopper’s wife, Jo ) sits on her bed facing the sun, looking out her bedroom window into a city sky. She appears to be lost in her thoughts as the sunlight enters from the outside of her window, illuminating her body and the otherwise dull bedroom. She is deep in her thoughts, looking at something - a sight situated outside the frame. Much like many of his paintings, the sight is ‘absent’ in the frame yet functions as the hidden object that nonetheless structures the condition of the subject and her desires. In his essay “Hopper and the Figure of the Room,” art historian John Hollander writes of Morning Sun that the parallelogram of the light cast against the wall behind Jo is “an image of the meditative gazer’s mind as the cast shadow on the bed is of her body.”

If we look at the original meaning of the word ‘virtual’, it comes from the Latin word virtus meaning 'a power of acting without the agency of matter' that is 'functionally or effectively but not formally of its kind. That is to say, the objects in the realm of virtuality cause an effect on the onlooking subject without being physically present in its materiality. We find this happening in the Morning Sun and in all of Hopper’s paintings. With his introduction of windows as ‘screens’ in almost all his paintings, the presentation of the object is often hidden, there is a trace of the other but it is never fully revealed. In his Morning sun, the woman is looking at ‘what’? ‘Who’ are the ‘Nighthawks’? There is an interrogation in the place of the object, that is, the objects are hidden or missing which triggers our desire to see more. This creates a possibility of inter-pictorial dialogue between the virtual Hopper and the audience and we are introduced to mental images which imprint themselves in the place of these objects. As mental images are produced in the imaginary domain of our perception, we are introduced to a fantasy surrounding the predicaments of subjects in his paintings. We try to imagine a relationship between the man and the woman sitting closely inside the cafe in “Nighthawks’ and we try to look out from the woman’s window in ‘Morning sun’ Finally, the desires of these subjects become our own desires. Hopper’s paintings function no less than what effect motion pictures ( cinema ) bring on to the audience. In Henry McBride’s words, Hopper’s paintings resemble ‘the slowest of slow-motion pictures'. To explain the paradox of the slowest motion in something that should by definition remain still, we can suppose that the paintings made the critic look at them through the prism of the film: the impression of slow movement comes from the combination of the internal quality of Hopper's work (residing in framing, perspective, etc.) and a remembered filmic image virtually superimposed on the screen of the critic's vision. The result is a kind of a struggle between the material and mental, a work of stimulating, intermedial difference.

No wonder that in 2019 the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts had curated an exhibition where every detail of his painting ‘Western Motel’ was brought to life by creating a room with the actual objects from the painting, offering guests the experience of staying the night. Afterward, the New York Times came up with an article with the heading “What’s better than seeing a Hopper Painting? Sleeping in One.”

In the post-modern age of subjectivity, Edward Hoppers’s realism feels less and less representational and all the more inter-subjective and cinematic, all too un-real.

References:

- Filip Lipiński. “The Virtual Hopper: Painting Between Dissemination and Desire” Oxford Art Journal, 2014, Vol. 37, No. 2 (2014), pp. 157-171 Published by: Oxford University Press

- This Edward Hopper Painting Has Been Called One of the ‘Ultimate Images of Summer’, Katie White, July 21, 2020

- Matt Backer. “Edward Hopper: An Artist in Pursuit of Desire” Resource Library, March 23, 2006