Blog

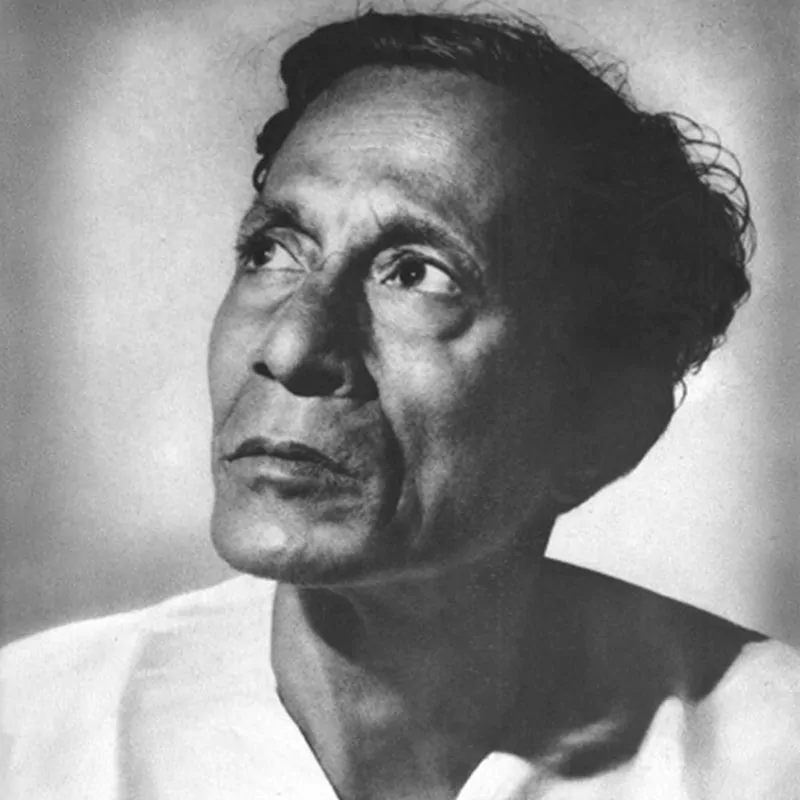

The Landscapes of Gopal Ghose.

A brief insight on the landscape paintings of Gopal Ghose.

Shyamal Dutta Ray: Watercolour Maestro.

A brief understanding on the art of Shyamal Dutta Ray.

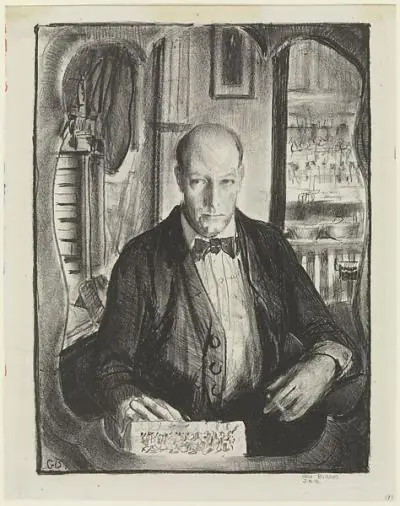

The Majumdar Siblings.

Understanding the artistic and literary works of Kamal Kumar Majumdar, Nirode Mazumdar and Shanu Lahiri.

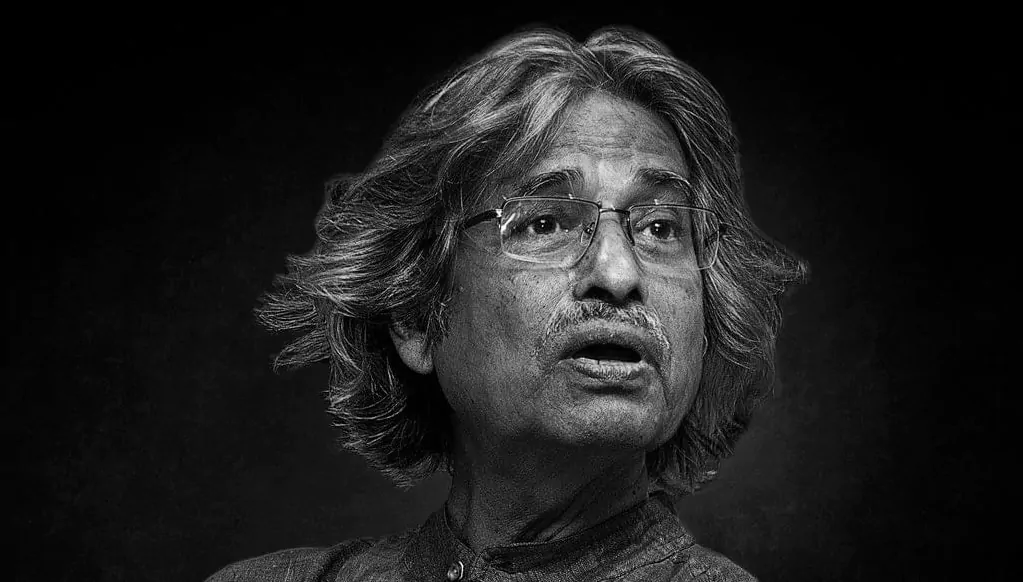

Jogen Chowdhury-A Man of All Seasons.

A critical appraisal of Jogen Chowdhury's Work.

Krishen Khanna: Last Man Standing

A brief appraisal on Krishen Khanna.

The Babu Culture: Through Lalu Prasad Shaw

A critical appraisal of Lalu Prasad Shaw.